A question we are often asked is “What type of entity should my business choose for income tax purposes?” These so-called “choice of entity” issues are, of course, important for startup enterprises, but they can be even more important for successful, established businesses.

There are two general types of business tax classifications. In the first category are businesses taxed at the entity level as corporations under Subchapter C of the Internal Revenue Code, called “C corporations.” The second category consists of so-called “pass-through businesses” whose income is “passed through” and taxed to the individual owners of each business. The first category consists of entities that either are or have elected to be treated as corporations for income tax purposes, and that have not elected to be treated as S corporations, which are “passthrough entities” taxed under Subchapter S of the Internal Revenue Code. The “pass-through” category consists not only of S corporations, but also limited liability companies, partnerships, sole proprietorships and other non-corporate enterprises that have not elected to be treated as corporations for income tax purposes.

C corporations are subject to tax at the corporate level when income is earned, and their shareholders are taxed again if and when that income is ever distributed out to them. “Pass-through businesses” are generally not subject to any tax at the entity level. Instead, their income is taxable directly to the owners of the business, something that is important to keep in mind when drafting Shareholder Agreements and other operating documents for these entities.

Figure 1 below shows top marginal rates for various types of business entities and income. The initial entity-level top tax rate for C corporations is only 35%, and can be even lower, 15% on the first $50,000 of income. But even the top rates are 5% to 10% lower than those applicable to “pass-through business” owners (43.75% through 44.59%).

But that is only half of the story. The 15% to 35% C Corporation tax is only the first tax that could apply to those earnings. If they are ever distributed out to the shareholder to be used by his or her family, there is another tax imposed upon those “dividends.” This raises the overall effective tax rate on these distributed earnings to more than 50%, and that is before taking any state income taxes into account.

[Figure 1 – Marginal Tax on Additional Income]

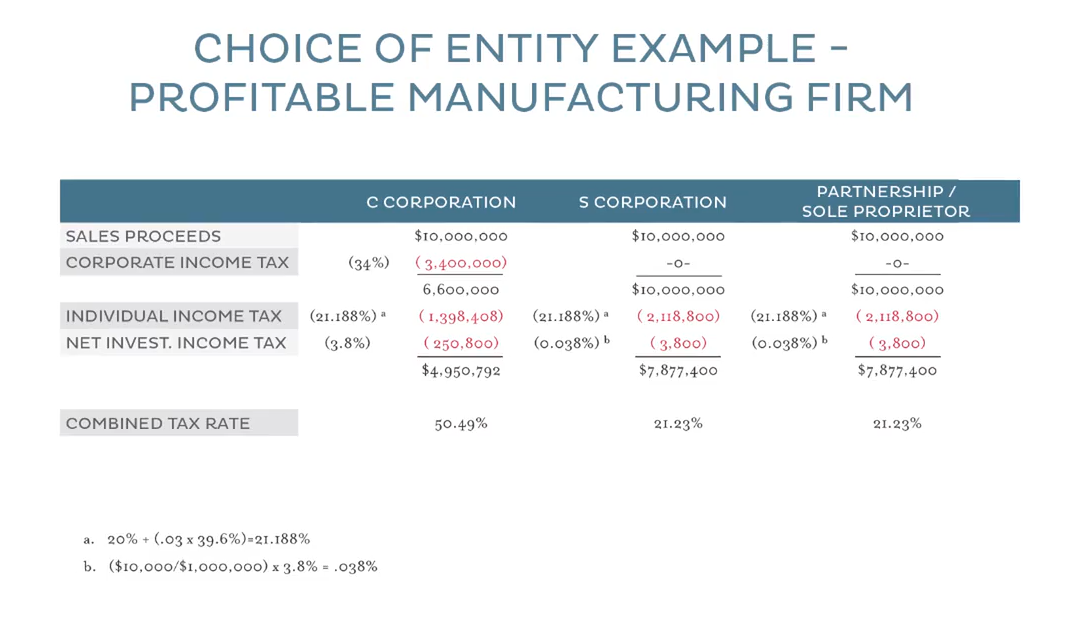

This can make a huge difference upon the sale of the business. An example can help to illustrate this dramatic impact. Below is a list of typical assumptions for a profitable manufacturing firm that earns $1 million of income per year:

- Owners in top tax bracket, over § 1411 FICA/SE tax threshold, active in business (non-trading) & paid reasonable compensation

- Entity level earnings $1,000,000

- Not a personal service corporation

- Partnership income subject to self-employment tax

- No basis at entity or owner level

- No § 1202 stock, but long-term capital gain

- No state income tax

- Owners qualify for simplified calculation of net investment income under Reg. § 1.1411-7(c) ($10,000 portfolio income, $990,000 trade or business income each of the last three years)

Suppose the owner has the opportunity to sell the business for, let’s make it easy, 10 times earnings, $10 million. For a number of reasons, most buyers will want to buy the assets of the business directly from the entity, rather than buy the stock or other ownership interests of the entity itself.

Figure 2 shows the substantial tax cost of C corporation status in this typical sale scenario. There are plenty of complexities here too, but just a couple of things. First, there is no capital gains tax break for sales of assets inside C corporations. Thus, the initial 34% tax at the C-corporation level is already almost 10% more than the final tax for S corporation, partnership and sole proprietorship “pass-through businesses” (21.23%). It gets worse. Sooner or later, the selling owner is going to want to distribute the after-tax proceeds so that his or her family can live off them during retirement. For the “pass-through business” owner, these distributions are nearly always tax-free, but these distributions trigger an additional almost 25% tax (21.188% + 3.8%) to the C corporation owner. The bottom line is that the C corporation owner is facing an overall effective tax rate on sale of 50.49% versus a much more favorable rate of 21.23% for the “pass-through business” owner. That’s a difference of almost 30%. $3 million in this $10 million scenario. Again, that’s before taking any state income tax consequences into account. Even at this stage there is tax planning that can be done, but it typically cannot completely eliminate this dramatic tax difference.

[Figure 2 – Choice of Entity]

You may wonder whether this substantial differential applies for bigger or smaller transactions. Although each deal has its own unique characteristics, in general, the answer is yes. In fact, the differential actually gets slightly bigger for transactions in excess of $10 million. But we’ve also run the numbers for smaller transactions, such as $500,000. Surprisingly, though the overall rates for both types of businesses are typically lower for these deals, we’ve found that there can still be a 30% differential. This can be even more discouraging at these levels, because there is less money to go around to begin with.

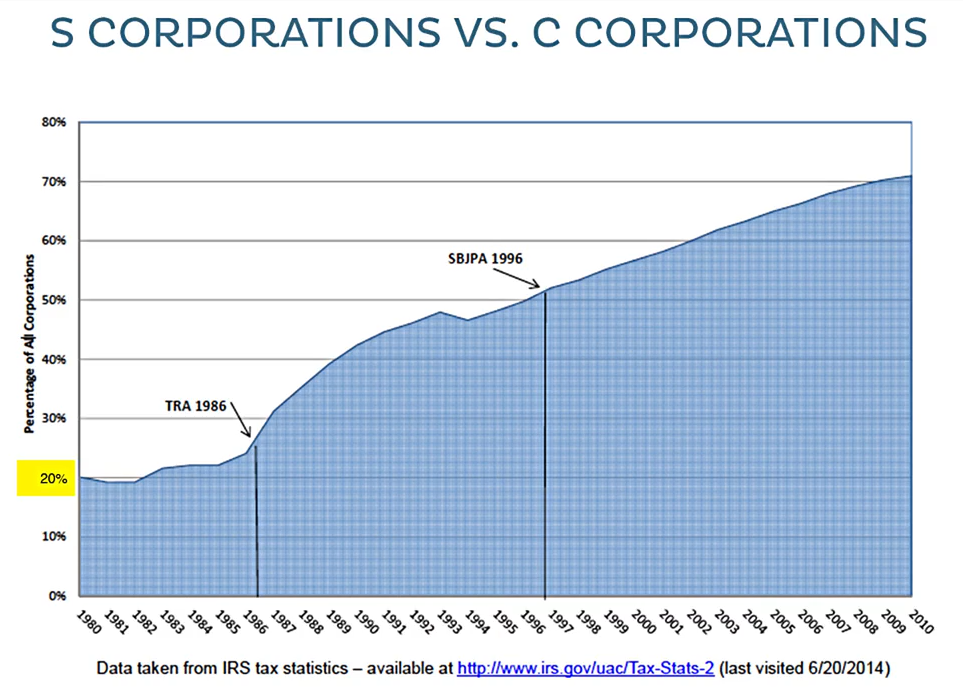

These tax dynamics have helped to cause a dramatic shift in tax classification for closely held businesses over the past 30 years. As you can see from Figure 3, while S corporations constituted only about 20% of all corporations before enactment of the Tax Reform Act of 1986, they now constitute more than 70%.

[Figure 3 – S Corporations vs. C Corporations]

In summary, whether you are an entrepreneur starting up a new business or the owner of an ongoing closely-held business, if you think you might want to sell your business sometime down the road, you really should consider “pass-through” tax treatment. We’ve handled a number of such conversions, as well as subsequent sales. Needless to say, facing retirement with an extra 30% of after-tax proceeds can make a big difference.